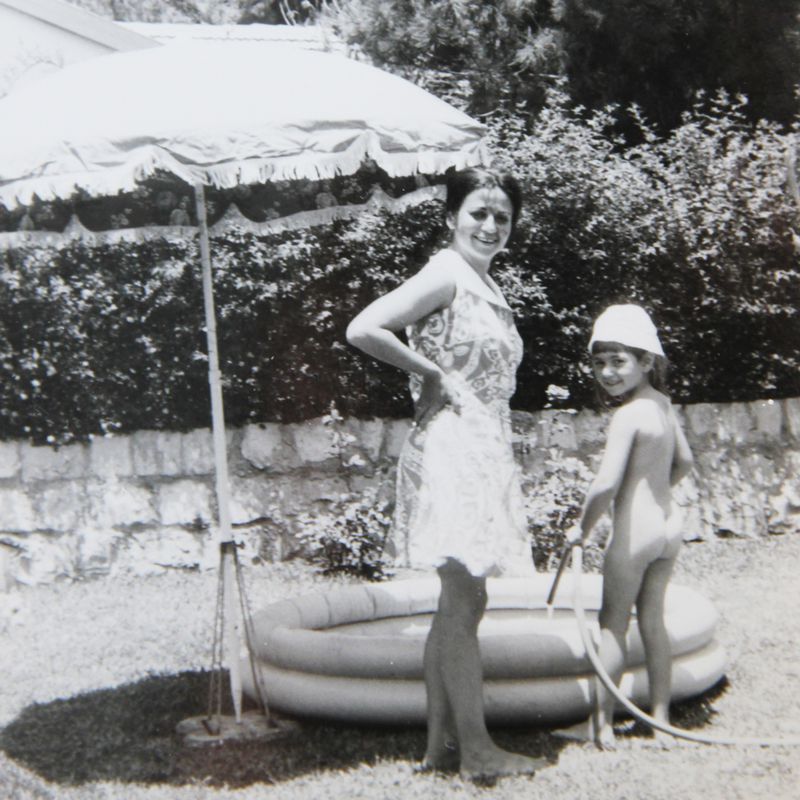

Ирит Ненер (имя при рождении в Нидерландах - Lea Winnik)

1932 – 2022, Нидерланды — Израиль

Ирит Ненер передала музею фигурки двух керамических птичек, покрытых серебром. Поделки находятся сейчас на вечном хранении у Светланы Головиной в Германии.

Попытка стенограммы.

Рассказ Ирит Ненер.

Записан 10.09.2019 Сашей Галицким в Ахузат Полег днем, с часу до трех пополудни.

— Когда эта Номи заговорила, я сразу возмутилась.

— Какая Номи?

— Ты ее не знаешь. Ладно, давай сначала поедим.

— Лехаим!

— Лехаим.

— Очень вкусно.

— Что не нравится — не ешь, я же не знаю твоих вкусов.

— Очень вкусно.

— Лосось, артишок, огурец, лакс, майонез. То, что нашлось дома. Оливок не было. Я всегда импровизирую.

— Я вчера опубликовал у себя в фейсбуке твою фотографию с Вангогом, помнишь, в моём проекте? В 2013 году? Так тебе очень много совсем незнакомых людей передало восхищение твоей работой и тобой лично.

— Я? Мне?! За что? Ты смеёшься. Что такого выдающегося я тогда сделала, что не делали другие?! Ок, не важно.

— Скажи мне, Ирит. Твой рассказ известен в музее «Яд Вашем»?

— Да. Конечно. То есть, нет. Они очень просили меня, чтобы я рассказала, но я не в силах это рассказывать. Я не хочу. Как тебе это объяснить. Я как солдат, вернувшийся с фронта. Я возвращаюсь с войны домой и не хочу вспоминать о войне. Я могу вспоминать о войне только в кругу таких же бойцов, как и я.

Это точно так.

Тут, среди нас сейчас нет никакого представления о том, что мы пережили. Обо всем, что касается Катастрофы.

И конечно эти, которые здесь родились, представления не имеют. Почему я возмутилась неделю назад? Сидят люди. Эта открыла большие глаза. Впервые в жизни она услышала что-то о Катастрофе! И это очень больно мне.

— Ты говоришь о Лее?

— Да, о Лее. И, кстати, и о Пинхасе и его покойной жене Ауве. Как-то мы вместе гуляли по Амстердаму. Там, где было гетто. Его уже там нет — убрали. Я им рассказываю. А Аува начала красить себе ногти посреди улицы! С кем я могу говорить?! Эти эпизоды настолько болезненны и я молчу. Никто не понимает. Только с людьми, прошедшее похожее, я могу говорить. Это понятно.

— Скажи, что знают про твою историю в музее «Яд Вашем»?

— Ничего. Что я жива.

— Они обращались к тебе?

— Да, несколько раз.

— И что?

— Мой муж сделал что-то для «Яд Вашем». Пойми, что эти нелегалы, эти неевреи, которые спасли нас — из сослали в Аушвиц, и они не вернулись. Они были верующие христиане, очень верующие, как наши хасиды. Это была группа молодых тогда еще людей, им было по 20 — 23 года, они спасли нас ценой своей жизни.

Они смогли спасти от смерти 250 еврейских детей.

Ты спрашиваешь о музее «Яд Вашем». Они перепроверяли нас, боялись, чтобы мы не нарассказали небылиц. И они назвали ту неизвестную группу, которая нас спасла «NV», то есть «Нелегальная организация».

Много других праведников мира получили в Израиле за спасение евреев медали, почет, и что бы ты не хотел.

А нам сказали: «Это безымянная группа, и мы не можем их записать в Праведники».

Так мой муж в конце концов навел с этим порядок. Они-таки получили в музее «Яд Вашем» признание.

... И был концерт. Меня спросили, какую музыку я хочу на вечере? Я заказала музыкантов. Они хотели завести заупокойную молитву. Но я сказала: «Нет!» Конечно, я не хочу слушать сейчас «Буги-вуги», но я хочу жизнеутверждающую и веселую музыку, ведь что может быть лучше того, что они для меня сделали, и что я сижу сейчас здесь, и что я начала новую жизнь, и у меня есть дети?!

Я думаю, что такую музыку играли впервые в музее, и это было очень здорово.

— Так значит, эта группа сейчас известна в музее?

— Да. Они спасли 250 детей, предназначенных для транспортировки в лагеря уничтожения. Они вытащили их можно сказать, из пасти льва. И спасли ценой своей жизни.

— Как им это удалось?!

— Разными способами. Дети до 16 лет были отделены нацистами от родителей.

— Взрослых евреев нацисты собирали в помещении Амстердамского драмтеатра. В зале на 300 человек находилось 4000. Это был пересыльный пункт. Дальше — Аушвиц.

Моим родителям было в ту пору 36 — 38 лет. Молодые совсем.

А дети. Дети. Напротив этого театра находился детский дом. Нееврейский, обычный. Немцы освободили его, и в нем находились дети евреев, сидевших в драмтеатре.

По нашей улице ходил трамвай. Такой, несколько сцепленных вагонов. Наверное водители этих трамваев что-то знали, или же недалеко была остановка, но, приближаясь к этому детскому дому, трамвай замедлял ход. Недалеко находился пост СС, но дети успевали убегать, скрываясь за медленно идущими трамваями.

Так дети убегали.

— Куда вы убегали?

— Куда глаза глядят.

Это был один способ. Хотя я сама за трамваем не бегала. Был другой.

Наши родители (не спрашивай меня как, я не знаю, мне было всего 10 лет), ухитрились вычеркнуть нас, меня и старшую сестру, из списков детей, находящихся в детском доме. То есть в списках детей, которые доплжны были отправится в Аушвиц, нас не было.

Мы нелегально там находились. Сестра старше меня на 3,5 года, тогда ей было 13,5.

И вот не раз и не два в середине ночи нас будили: «Дети, дети, скорее вставайте и бегите наверх! С крыши на крышу, и убегайте — проверка!» Наш старший воспитатель знал про это, и специально держал окна на чердаке открытыми. И мы убегали. Куда? Куда глядели наши глаза.

Таким способом мы с сестрой удирали в город.

— Сколько времени вы провели в этом детском доме?

— Недели две. В этом доме мы прятались, а удирали дважды.

— Как дважды?!

— Это длинный рассказ.

Мы с сестрой удрали. Две девчонки. Куда было идти? Каждую секунду нас могли схватить. Му хорошо знали Амстердам. Ночевать пришли на рынок и залезли под накрытые брезентом прилавки. Моросил дождь. Не такой ливень, как бывает тут, а моросил дождик такой, европейский.

Так мы спали под брезентом. Было не просто. Это трудно представить. У меня много историй. Подумай, надо было что-то есть, мыться и менять одежду. Холод. Дождь. И тут мы с ней вспомнили, что поблизости в доме на третьем этаже живет наша бывшая домработница.

Ну, хоть это. Мы поднялись к ней на третий этаж и зашли в квартиру. Она нам не сильно обрадовалась и сказала: «Дети, каждую минуту вас могут арестовать. Я не смогу вам помочь». Я стала плакать и кричать: «Я хочу к маме!»

Она подошла к окну и сказала: «Смотрите (это интересный рассказ). Смотрите дети. Вон там внизу стоит человек. Я слышала, что он помогает еврейским детям. Идите к нему.»

Он как раз стоял на перекрестке и с кем-то разговаривал.

Мы спустились. А что нам оставалось делать? Мы не могли оставаться у нее.

Я подошла к нему. Помню, он был очень высокий и в плаще.

И я сказала:

— Господин! — и подергала его за край плаща.

— Да, девочка, — ответил он.

— Я слышала, что ты помогаешь еврейским детям.

Он посмотрел на меня. Сестра зашептала: «Не говори ему больше ничего!», но я наверное была умнее ее и нам нечего было терять.

Он спросил:

— Как вас зовут?

Мы назвали наши имена и он сказал:

— Возвращайтесь в Крэш (Крэш — это был тот детский дом, в котором собрали еврейских детей), — вы возвращаетесь в Крэш, а я вытащу вас оттуда, КОГДА ПРИДЕТ ВРЕМЯ.

Так он сказал. Сестра моя начала выговаривать мне: «Погляди, что ты наделала! Теперь нам надо возвращаться, а он скорее всего просто эсэсовец. Он хочет, чтобы мы вернулись!»

Но так и случилось.

Потом нацисты поймали, пытали и отправили в Берген-Бельзен, где он и погиб.

— Как вы вернулись? Как? Вы же не могли вернуться через парадный вход?!

— Есть вещи, которые я уже не могу вспомнить.

— Как он вас оттуда вытащил?

— В этом доме находились две медсестры из клиники известного профессора Коэна. Профессор Коэн был там легально, с разрешения нацистов. Это известная история, потом его судили...

Так вот. Эти две сестры знали, что мы должны убежать. Однажды нас позвали вниз. Мы спустились. Там стояли две этих медсестры и незнакомый человек. Он поглядел на нас и сказал:

— Подойдет. Эта может сойти за индонезийку (а мы с сестрой совсем не были похожи), а эта может быть просто христианкой. Порядок. Дети, возвращайтесь наверх!

Вскоре мы получили приказ удирать опять. Мы должны были появиться по какому-то адресу в Амстердаме, а оттуда нас должны были забрать и куда-то переправить.

Это и произошло.

И начались мои поездки на поездах.

Нас с сестрой разделили.

И не разговаривать.

Так я спаслась.

— А что родители? Как вас поймали нацисты?

— До этого мы прятались всей семьёй. МЫ уехали из Амстердама и прятались. Нас кто-то выдал. Я помню эту ночь. Папа сделал потайную комнату под крышей какого-то дома. Это еще стоило много денег, прятаться!

И вот однажды ночью пришли нацисты: «Четыре персонен, раус, раус или мы открываем огонь!»

А что ты думаешь? Мы спустились, иначе они бы стреляли.

Они знали, что мы там.

И начались тюрьмы. Настоящие голландские тюрьмы. Родители сидели в одной камере, а мы с сестрой в другой.

Сказать тебе, что это было приятно? Нет.

Так мы переезжали из города в город, сидели в разных тюрьмах, пока не оказались снова в Амстердаме.

Это было в 1943 году.

Родители знали, что не вернутся. Раз в неделю нам с сестрой было разрешено на полчаса свидание с мамой и папой. (Когда они находились в драмтеатре).

И папа сказал: «Дети! Нам удалось больше 9-ти месяцев прятаться вместе от несчастий, и мы были вместе. Запомните. Скорее всего мы с мамой не вернемся. (Мама зашикала на него: «Не говори глупости!», но папа знал: «Ждите нас 25 лет. Если мы не вернемся — значит нас больше нет.»

Это были последние слова родителей.

Еще он сказал сестре: «Ты заботишься о Лее (меня тогда вообще звали Лея), ты старшая сестра. Но если вдруг настанет смертельная опасность, ты должна думать только о себе и спасаться любой ценой. И Лея — то же самое. Не думать о сестре.»

— Как звали твою сестру?

— Шела.

— Как ты стала Ирит?

— Уже тут, в кибуце, в Палестине. Там было уже до меня шесть Лей, и они не захотели седьмую.

Когда нацисты в 1940 году пришли в Голландию, все происходило постепенно. Голландцы есть голландцы. И не было ни у кого даже представления о газовых камерах. Все думали, что надо просто тяжело работать — и все уладится. О газовых камерах мы узнали только уже после войны.

Ну хорошо. Продолжим обед. Сейчас — суп.

— Скажи. Ты рассказывала обо все этом детям? Они знают?

— Я ни разу ни с кем об этом не говорила.

— Но я же не первый, кому ты это рассказываешь сейчас!

— Нет. Мой муж это знал. Правда, сначала он сам не представлял, потому что в это тяжело поверить. А дети — дети сначала обижались, а потом поняли, что не надо ни о чем меня спрашивать. Они до сих пор злятся. Они говорят: «Мама, скоро тебя не станет. Мы хотим знать, что ты пережила.» «Хорошо, дети», — отвечаю я, но дальше этого дело не идет. Знаешь, однажды, когда Яир (мой старший) был еще маленький, к нам в гости заезжал какой-то голландец из тех, кого мы знали по прошлой жизни, и в беседе я сказала ему: «Слава богу, что мои дети растут нормальными, и несмотря на то, что я пережила Катастрофу, они этого на себе не ощущают.» «Это тебе так кажется, мама», — сказал мне тогда маленький Яир. Я всегда хотела, чтобы дети были просто обычными нормальными детьми. Но мне это все просто невозможно забыть.

— Когда у тебя родились дети?

— Яир родился в 51-м, а Анат в 64-м. Да. Я спешила родить Анат, чтобы она успела на бар-мицву к брату (смеется).

— 13 лет разница?!

— Я сделала холодный суп. Может, тут недостаточно соли, я боялась. Посоли сам. Представь себе, как ребенку было сидеть в тюрьме. Ни уборной, ничего. Ходить на ведро. Я все время об этом думаю.

— Суп. Гаспаччо!

— Ой-ой-ой. Истории... И это только маленькая часть моей жизни. Ты спрашиваешь, как это все происходило в Голландии... Потихоньку. Сначала евреям нельзя стало ездить на велосипедах. Потом меня перевели в специальную еврейскую школу, потому что совместное обучение евреев и неевреев запретили. Потом жгли книги. Потом нам разрешили покупать продукты в лавках только с часу до трех пополудни, и не все продукты там находились. Потом комендантский час с 20 часов. Потихоньку закручивали гайки.

— Сядь, сядь уже.

— Хорошо, сажусь. Давай есть суп. Это моё изобретение, этот суп. С хлебными сухариками. Я их жарю с чесноком в оливковом масле. Бросай, бросай, бери еще и ешь, пока хрустят.

— Спасибо. Ну вот, так ты переезжала 22 раза из одной семьи в другую. Почему 22?

— Или вдруг опасность и надо быстро исчезнуть. Быстро-быстро убегать, ночью. Или вдруг хозяевам надоело меня видеть. Или еще черт знает что. И надо убегать. По ночам. Днём я не появлялась на улице. Ты думаешь почему сейчас у меня больная спина и четыре позвонка не на месте? У меня еще отекали ноги от голода.

Была голодная. Даже уже когда кончилась война мы еще делали чай из листьев. Иногда от крестьян перепадала бутылка молока, и тогда в мои обязанности входило болтать эту бутылку до тех пор, пока на донышке не оставалось немного масла! Это на Рождество!

Я не была уже еврейкой. Я была протестанткой. Я была святее папы римского, хоть он и католик.

— Ты жила во многих семьях. Как к тебе там относились? Тебе было неплохо?

— И да и нет. И да и нет... Этим людям в основном платили за нас, чтобы они нас прятали. А что ты думал?! Нет, были среди них некоторые, которые прятали нас за место в раю, которое они получат, если они спасут от смерти еврейку-христоубийцу (смеется). Наверное.

— Я жила у протестантов. Некоторые были симпатичные, а некоторые совсем нет.

— А как ты себя чувствовала среди детей? Твоих ровесников?

— Плохо. Дети все прекрасно понимали, кто я, и делали со мной, что хотели. Мне некому было пожаловаться. Однажды... Я примерно знала, где находится моя сестра... Я пошла ее искать. Знаешь, там был такой сарай что ли... Он меня изнасиловал. Он был парень наверное лет 18-ти... Я ничего не поняла. Мне только было очень больно. Я зашла в какой-то дом и рассказала. Они все сразу поняли и позвонили священнику. Он сразу примчался на велосипеде и забрал меня. Я прожила у него два дня и уже должна была уходить. В ту ночь, после того, как я ушла, к нему ворвались нацисты и расстреляли его прямо во дворе. Он был подпольщик.

Ешь-ешь, пока не размокли сухарики.

Я правда скажу тебе, что я ничего не поняла, что этот парень со мной сделал. Мне просто было очень неприятно и все болело.

Это только часть моего рассказа. Пойди-ка все расскажи! Об этом можно написать десять книг!

Но это невозможно рассказать.

— Очень вкусный суп.

— Ешь еще, ешь. У меня теперь останется еды на неделю. Свежие помидоры. Что-то еще я положила... Соль. Перец. Порошок куриного бульона. Я знаю что?! Немного этого... того... Соя... И кусок хлеба, чтобы суп стал погуще! И все размешала блендером.

И сухарики. Я добавляю их всюду. И в борщ. Холодный свекольник, со сметаной. Объеденье! И зимой. В гороховый суп. Ешь, останется полно еды…

— Да. А как ты выбралась из Голландии ? Что было после войны?

— Когда закончилась война (не знаю поверишь ли ты мне или нет), случилось вот что. Эта история, как и многие, «Началась за здравие, а кончилась за упокой». После войны мой родной дядя (папин брат) искал меня. Вся его семья погибла в Катастрофе, он остался один. И он стал разыскивать всех родных, кто остался. Тут ребенок, так чья-то жена. Он снял для этого огромную 12-комнатную квартиру.

Он был еврей, с таким носом, но еврейских традиций он не знал совсем. Он подобрал меня. Но у меня на все, что касалось христианства, был готов ответ.

Ему со мной было тяжело. Я была сильнее его по характеру.

А потом появилась какая-то женщина, вернувшаяся из Аушвица. Не его жена, но чья-то далекая родственница.

И она совсем не захотела видеть меня в его доме. У меня началась ужасная жизнь. Скандалы. Снова начался ад.

Она хотела от меня избавиться, я слишком много о ней тогда знала.

Однажды. Однажды случился очередной скандал. Дядя меня ударил. И я ему ответила.

Он сказал мне: «Уходи.» И я ушла.

И вот я иду-иду. Это был вечер субботы. И вдруг я увидела дом, а на нем еврейские буквы. Откуда я знала еврейские буквы?

Рассказывают, что мой папа когда-то очень давно, будучи сам ребенком, учился то ли в каком-то еврейском семинаре, то ли в синагоге, я не знаю точно.

А у моей бабушки (его мамы) уже в те далекие времена был пылесос. Однажды в субботу она принялась пылесосить, а мой папа сказал ей, что евреям в субботу нельзя этим заниматься. Она ответила ему чем-то вроде: «Кто ты такой, чтобы приказывать в моем доме чем мне заниматься, а чем нет и когда?!», на что папа обиделся и ушел из дома. На полгода. А вернулся заядлым атеистом.

Так вот, я тоже не получила от него дома, в детстве, никакой религиозной еврейской культуры.

— Ну, так ты увидела на то доме еврейские буквы, и что было дальше?

— Да-да. Так вот. Я поняла, что это иврит.

Начал дождь. Я постучалась в этот дом. Уже было воскресенье.

Мне открыла дверь какая-то женщина и спросила что мне нужно?

Я сказала, что меня зовут Лея Винник (так меня тогда звали) и я спросила ее (смеется): «Госпожа, что такое кибуц?»

Она посмотрела на меня внимательно и спросила где я живу? Я ответила.

Она пригласила меня выпить кофе.

Оказалось, что вся ее семья тоже погибла во время войны.

Мы подружились. Она стала для меня всем.

Впоследствии она помогла мне перебраться в Палестину.

Я добиралась через Париж, через Марсель. В парижском вагоне впервые я повстречала настоящих еврейских хасидов, с белыми бородами и в черных шляпах. Я не поняла тогда, что это за «монахи» такие?!

Я прибыла в Палестину на первом легальном иностранном судне еще до начала войны за Независимость. Судно называлось «Трансильвания».

Мне было 16 лет.

— Ирит, а кто были твои родители? Чем они занимались?

— Мои родители владели пошивочной мастерской. Папа был один из самых известных местных портных, он одевал мужчин в Амстердаме.

Я помню, как сидела на длинном столе в его ателье и смотрела, как он работает. Мне было 5 лет. Иногда, когда ему надо было снять мерки с клиентов, папа говорил: «А сейчас ты идешь играть!»

— Очень вкусно. Ты должна это все рассказать детям.

— Знаешь Саша, разочарование — это очень страшная вещь. Когда идет война, ты ждешь ее окончания и мечтаешь о счастливой жизни потом. А тут, сейчас, у людей даже нет никакого представления, что мы испытали.

Хорошо.

Сейчас — второе блюдо.

— Ты сошла с ума. Я должен все это сфотографировать.

— Это — рис с баклажанами. Ой, я забыла солила ли. Не успела сделать еще один салат, но у меня есть. Это кисло-сладкое мясо.

Помоги мне.

— Ирит, садись уже. Уже всего достаточно, хватит!

— Посоли, если тебе надо.

— Вина?

— да, конечно.

— Лехаим.

— Лехаим.

— Ты ждала 25 лет отца и мать? Тебе известно что-то об их судьбе?

— Немного знаю. В ту же неделю их забрали. Папу — в Аушвиц. Маму — в Биркенау.

— Папа еще был жив. Долго. Он умер в лагере только в 44 году, когда уже наступали русские. Он умер в снегу. О маме я не знаю ничего. Ее забрали на эксперименты? Не знаю.

Так что меня возмутило тогда, в тот день. Это очень трудно говорить о нашей «Святой земле». «Эрец Исраэль»... Все началось с Номи. Она одна из наших, живет тут неподалеку. Она решила открыть для стариков в нашем доме кружок немецкого языка. Разложила в почтовые ящики приглашение и внизу приписала: «Говорить по-немецки — это очень мило!»

Я пришла на первое занятие. И сказала. Я сказала: «Номи. Я не езжу в Германию. Конечно, раньше, когда я путешествовала, мне транзитом приходилось останавливаться иногда в германских аэропортах. Чтобы не смущать своих попутчиков, я старалась не устраивать из-за этого проблем. Я понимаю, что тут, сейчас меня мало кто поймет. Но явиться в наш дом престарелых и утверждать, что говорить по-немецки — «это очень мило?!» Не слишком ли?!»

На первой встрече было человек 20. Номи спросила меня, почему я не хочу говорить по-немецки?

Я ответила ей, что она, которая приехала из Германии до войны, еще в начале 30-х маленьким ребенком, меня понять не сможет. Что из того, что потом она была или директором или завучем какой-то спец. школы в Нагарии. Я сказала ей, что пришло время объявить, что по-немецки я говорить не хочу и кружок ее посещать не намерена. Все замолчали вокруг. Номи мне ответила, что она лицно очень любит Германию, ездит туда, и с удовольствием отдыхает вместе с ее немецкими друзьями в местных домах отдыха. Поэтому она уважая, мою точку зрения, останется при своей.

Знаешь, больнее меня трудно было ударить. Я еще раз поняла, насколько люди тут не представляют и не знают, что мы пережили. Не знают!

Возьми мясо. Я всегда импровизирую.

Что случилось с той группой голландцев, которые нас спасли?

Некоторых из них нацисты поймали и после пыток отправили в лагеря, к евреям.

Они погибли.

Аушвиц, Берген-Бельзен, Биркенау, Бухенвальд.

Их самого главного они очень пытали.

А тот, помнишь, который в плаще стоял на площади, и к которому мы с сестрой подошли и подергали за плащ — погиб в Берген-Бельзене.

А мою сестру прятали (я этого тогда не знала) в его квартире, в Амстердаме. Мою сестру спасла его жена.

Ешь, ешь. Я не знала, не вегетарианец ли ты, на всякий случай приготовила рис. Жалко, что не спросила тебя раньше. Вкусно? Ну, здорово.

— А кто был твой муж?

— Мой муж спасался в Швейцарии. Там тоже было не сладко. Об этом тоже мало что известно людям.

Его звали Ханох. В 22-м году он со своими родителями перебрался из Польши в Голландию. Но его семья так и не получила гражданство, потому что гражданство стоило больших денег, которых у них не было. Они так и остались в Голландии нищими польскими эмигрантами. Гражданство ему было сразу предложено после войны, но мой Ханох был сионист, он не захотел оставаться после войны в Европе и оказался в Палестине.

Сейчас бы он наверное перевернулся в гробу, если бы узнал о Номи и ее кружке немецкого языка в нашем доме.

Ханох был красавец.

Что с ним стало в конце? В конце он был болен. А в начале он прибыл в группе из 600 молодых людей, собранных по всем лагерям. Сначала их приводили немного в себя в Швеции.

И тогда, когда как раз взорвали улицу Бен-Иегуда в Иерусалиме, они прошли с флагами по улицам. Они были красавцы.

Он шел в голубой рубашке, молодой, с флагом, впереди всех. И пели марш (поет): «ла-ла-ла-ла..., эти слова написаны кровью..., ла-ла-ла-ла». Ну, ты знаешь этот марш (я нет - S.G.).

Мой муж... Мы сначала жили в кибуце. Началась корейская война, он решил забрать своих родителей к нам. Мы покинули кибуц.

Потом Бен-Гурион обратил на него внимание...

Потом, если очень кратко, он стал первым мэром города Эйлат. Да-да-да! Какое там было море, ты себе не представляешь! Там было пусто, совсем пусто. Никого.

Потом он был консулом в Чикаго, во Франции.

Потом заболел раком. До этого у нас еще была автокатастрофа. Лобовое столкновение с грузовиком недалеко от Хайфы, дороги номер два еще тогда не было.

Я была с сыном, с Яиром. И это еще было счастье, что мы были в фибергласовой «Сусите», а не в настоящей машине. Иначе нас бы уже тогда не было.

Начались операции. Муж, сын.

Я сказала ему, что семья мне дороже всего, и что я хочу, чтобы он оставил дипломатическую службу, тем более, что сын остался нездоров.

Без второго слова он меня послушался.

Потом он заболел. Болел он долго, пять лет, и в 1992 году умер. Ему было тогда 69.

Одну вещь скажу, Саша. Моя жизнь не была скучной. От взлетов до падений. От ужаса до безграничного счастья.

— А ты сама? Кем ты была? Ты смогла учиться?

— Да, это было так. Сначала я волонтерствовала в Эйлате в одной из больниц. Я помогала делать анализы и научилась проверять их через микроскоп. У меня получалось! Профессор Гранот послала меня учиться на курсы, прислала мне хороший микроскоп, и так началась моя карьера! (смеется).

А потом в Чикаго я отучилась на бакалавра в университете. Моя профессия микробиология.

— Скажи, ты передавала имена своих погибших в «Яд Вашем»?

— Нет. У них вообще записано, что я находилась в лагере Аушвиц. Это ошибка. Хотя в Амстердамском музее есть наша с сестрой фотография в экспозиции. Но настоящая моя история неизвестна в «Яд Вашем».

— Ирит, я напишу про тебя на русском. Мы тоже мало знаем. Я вырос в СССР. Нам не рассказывали про геноцид евреев. Нам говорили, что погибло много «гражданского населения». Я сам ничего не знал.

— Сейчас — десерт. Это дыня и киви.

Ешь.

Ханох был старше меня на десять лет.

Скоро я пойду за ним.

Хранитель Светлана Головина

Германия

Светлана родилась в Алма-Ате, работала в Хэседе и Сохнуте, изучала еврейскую историю и традиции. На настоящий момент является хранителем Двух птичек Ирит Ненер.

Две птички

Материал: керамика

Техника: круглая скульптура, покрыта тонким слоем серебра

Вес: 293 гр

12297